The origins of sugar

Sugar has changed the course of history and its story is extraordinary. It beats tea and coffee as a commodity that has changed the world. Its central role in the Triangular Slave Trade and colonial history has an impact on our society to this day.

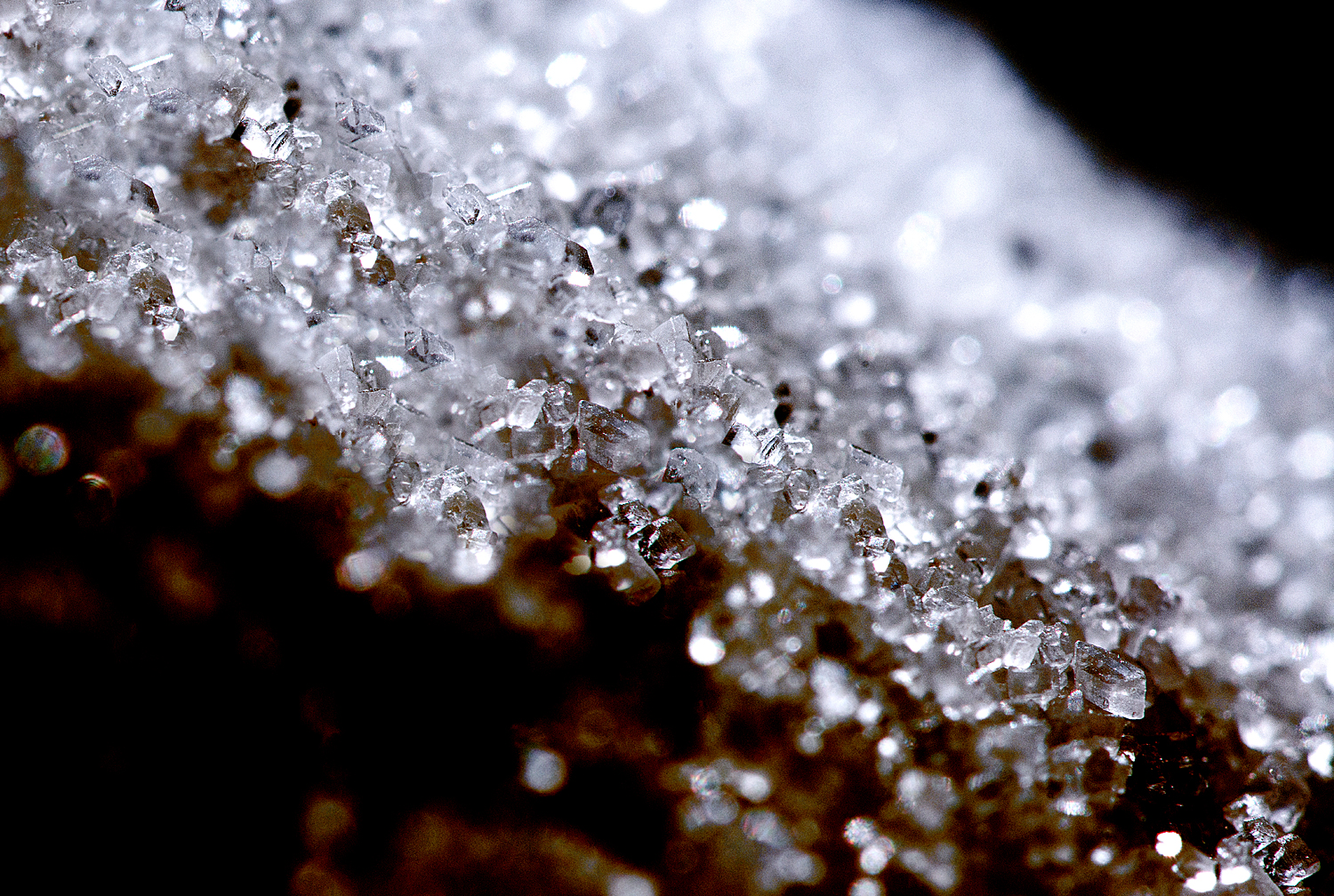

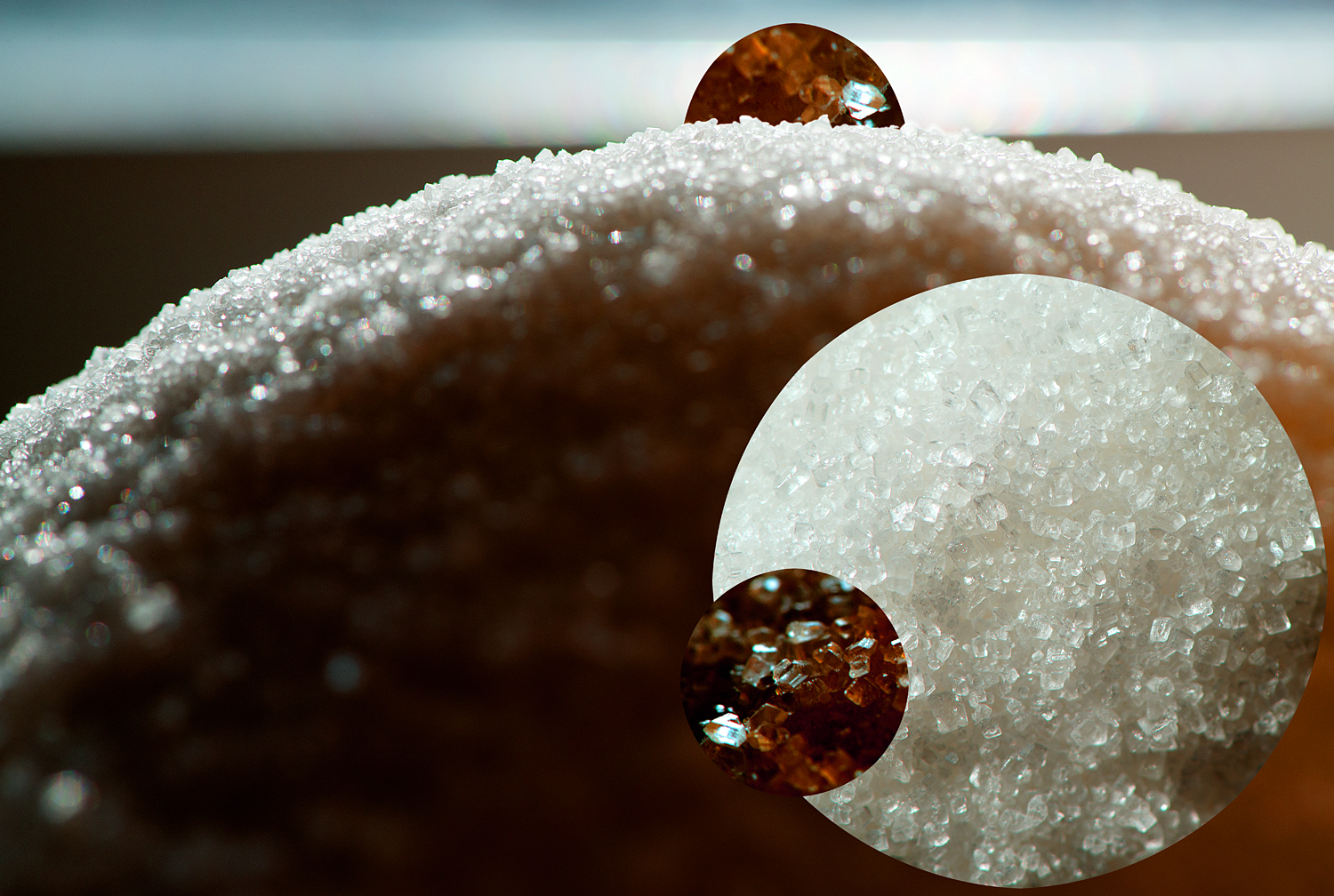

Of all the plants, one species of sugar cane, Saccharum officinarum, contains the most sugars. From the tropics of South East Asia, it was domesticated as long as 8,000 years ago and harvested for its sweet juice. The crystallisation of sugar is a complicated chemical process and this probably began in India about 2,500 years ago. From Asia, sugar cane cultivation spread to the Middle East in Roman times, then around the Mediterranean during the Arab Empires. Sugar cane is a tropical plant: it needs both a lot of warmth and water, which explains why the Nile delta in Egypt became an important centre. From the 10th century Venice dominated the sugar trade, importing it into Europe. Sugar was a very expensive commodity then, reserved for the wealthy.

Sugar production is very labour intensive. In the Middle Ages, wars and the Black Death led to labour shortages and the use of slaves in the plantations around the Mediterranean became common practice. Both the dry, unsuitable Mediterranean climate and local deforestation led to a decline of the industry. The rise of the Ottoman Empire was also disrupting the supply of sugar into Europe. As a result, European powers started to search for new lands to grow sugar.

The triangular slave trade

The Portuguese and Spanish Empires were the first to establish new sugar plantations on islands off the west coast of Africa, then later in the Gulf of Guinea in tropical Africa. Sugar cane was introduced in the West Indies by Christopher Columbus from Spain in 1493. The Portuguese then colonised Brazil and established a thriving sugar industry there using indigenous slave labour and the technological improvements they had learned from their African plantations. With diseases introduced from Europe decimating the Brazilian population, the sugar barons decided to establish a slave trade from Africa, using ships crisscrossing the Atlantic.

Ten to twelve million Africans were enslaved and shipped across the Atlantic as part of the Triangular Trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas. Manufactured goods (arms, textiles, wines) were sent to Africa from Europe, slaves were shipped from Africa to the New World plantations, commodities (mainly raw sugar and coffee) were sent from the colonies to refineries and commercial centres in Europe and North America. The colonies were made to rely on the mother countries for most of their supplies and all the profits from the plantations were exported to Europe.

By the late 16th century, Brazil was dominating the world sugar production. Then British, French and Dutch colonists joined the bonanza. Plantations and raw sugar processing mills took over the West Indies, parts of South America and later the southern colonies of North America. The production of the refined sugars took place in Europe, with the cities of Antwerp, London, Bristol, Bordeaux, as well as New York replacing Venice as centres of the trade.

The industrial revolution

The 16th and 17th centuries are viewed by economists as a transitional period between feudalism and capitalism, with trades such as the Atlantic sugar trade being instrumental in enabling the Industrial Revolution of 18th century Britain. The transfer of all the profits to the homeland, the total exploitation of the slave labour, the relentless appropriation of the colonial land and its natural resources, the economic subjugation of the colonies, all were important factors in creating the vast wealth which enabled the new capitalist industries to later emerge in Britain.

The early 19th century’s Napoleonic wars brought in a new player in the sugar story: the sugar beet. The plant Beta vulgaris originates from the Mediterranean. It is a very hardy root vegetable naturally rich in sugars, widely grown in Europe at the time because it made great fodder for cattle. Previous attempts in Prussia at the commercial extraction of beet sugar had not been a success. During the Napoleonic wars, a revolution in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti) and a British blockade of French ports led to a shortage of cane sugar in France. Napoleon’s government financed the study of sugar beet and rapid progress was made in the manufacturing process. Beet became a competitor to sugar cane, gradually becoming the main type of sugar in Europe. Its cultivation greatly contributed to the price of the commodity plummeting over time.

Slavery was abolished during the 19th century. Plantation owners responded to labour shortages by using a more modern form of slavery: indentured labour. Poor people, mainly from India but also China and other countries, were recruited (often tricked) to work for a period of 5 years on plantations across the oceans. Wages were very low and conditions harsh. Worldwide, sugar markets were expanding, with plantations established in new areas. Globally, the price of the commodity fluctuated widely, gradually following a downwards trend as more was produced more cheaply.

Throughout its history, sugar has been a highly political commodity. Its trade played a part in many conflicts between European empires. In America, anger caused by heavy import tariffs on rum, a by-product of the sugar cane industry, was influential in starting the war of independence against Britain. The American Civil War was caused by southern states refusing to abolish slavery in their cotton and sugar plantations.

More sugar history to follow after the artwork...